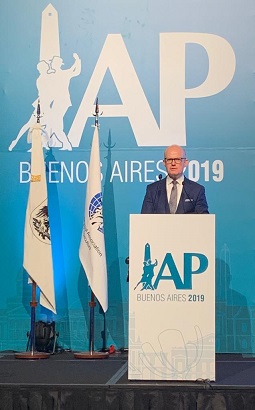

Tackling Global Crime Together - Speech by Max Hill QC, DPP, to the International Association of Prosecutors, September 2019

Conference in Buenos Aires

The International Association of Prosecutors (IAP) is a hugely important organisation for prosecutors, with an unparalleled global reach. I am therefore privileged to have been asked to deliver the keynote speech at this conference. This is my first annual IAP conference as chief prosecutor of my country, and so I am very pleased to be here and to have the opportunity to build relationships that will last over time.

The International Association of Prosecutors (IAP) is a hugely important organisation for prosecutors, with an unparalleled global reach. I am therefore privileged to have been asked to deliver the keynote speech at this conference. This is my first annual IAP conference as chief prosecutor of my country, and so I am very pleased to be here and to have the opportunity to build relationships that will last over time.

The theme of this conference is international cooperation; this is a wide ranging topic, and one in which we all have some experience - some good, and unfortunately some bad.

The reality is that international cooperation is now an essential component of modern investigations, prosecutions and asset recovery. It is something in which we must all be involved. I’m sure over the next few days we will hear of the many challenges faced by prosecutors seeking cooperation across borders and also, I hope, some of the successes from which we can all learn.

I would like to take this opportunity to share some of the challenges in securing international cooperation which are specific to the UK, as well as more general challenges, to reflect on how the UK makes it work, and finally to suggest what we need to do in the future.

First I’d like to mention the scale of the crime threat we all face, as this puts the importance of international cooperation to tackle crime in the correct context. Last year the UK government estimated that serious and organised crime costs the UK at least £37 billion annually. This threat includes economic crime such as money laundering, fraud, bribery and corruption, as well as cybercrime, smuggling in people, drugs and firearms, and child sexual exploitation. The number of fraud offences rose to 3.64 million in the UK in 2018, making it the second most prevalent crime type and constituting a third of all crimes in the UK. At least 84% of frauds are estimated to be cyber enabled, and therefore likely to have an international element. Money laundering ranges from cash-based money laundering, including through money mules, to using complex financial systems for high- end money laundering. The UK’s National Crime Agency believes the majority of serious and organised crime in the UK has “a clear international dimension”. This means organised criminal groups source illicit commodities, exploit vulnerable people and defraud UK citizens and businesses from overseas and transnational criminals continue to exploit vulnerabilities, such as those at our borders, to commit crime in the UK and overseas. This impact is likely to be replicated globally and we are therefore all faced with a challenge in terms of volume, scale, and complexity.

Cooperation with the UK

Moving on then to challenges to international cooperation, and I’ll start with the challenges of dealing with different legal systems by looking briefly at the UK.

The UK itself has three different legal jurisdictions (England & Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland) and the roles and responsibilities of prosecutors are distinct in each. Moreover, the UK has had effective and long standing close cooperation with many EU Member States who follow the civil law tradition or mixed civil/criminal law systems.

One of the key differences in England & Wales, compared to the majority of countries, is that role of the prosecutor; the Crown Prosecution Service and law enforcement are independent of each other.

Although prosecutors provide advice, sometimes early in an investigation, we cannot order law enforcement to take a particular action, we do not direct investigations, and we do not authorise search warrants.

When making decisions to prosecute CPS prosecutors apply the test in our Code for Crown Prosecutors. This has two stages. Firstly, there has to be sufficient evidence to provide a realistic prospect of a conviction, and secondly a prosecution has to be in the public interest. This means that prosecutors have discretion and this gives the system as a whole flexibility.

This flexibility and the application of the public interest test mean we can use alternatives to prosecution, we call this diversion, such as the administration of conditional cautions or fines through a penalty notice for less serious offending. In some cases this may push an offender on a more structured path away from future offending and reduce the risk of re-offending. We tread carefully here, but the emerging evidence shows that it can work well.

In practice when it comes to international cooperation the discretion available to the prosecutor may mean that we are not obliged to pursue a prosecution, and this may mean we make less use of international tools. I appreciate that not all systems have this discretion and some are strict in regard to what the prosecutor has to pursue.

The role of a CPS prosecutor also has an impact on the way we approach international cooperation, and therefore the way you will interact with prosecutors in England & Wales.

The CPS is heavily involved in extradition and asset recovery work, and we are responsible for issuing outgoing extradition requests, Interpol Red Notices, and obtaining European Arrest Warrants. The CPS Extradition Unit conducts extradition proceedings on behalf of foreign authorities for ‘requested persons’ arrested in England & Wales. This work results in around 1,000 wanted persons being extradited each year.

On asset recovery, the CPS issues requests for restraint and confiscation, and for EU requests we act as a central authority for both transmitting these requests overseas and for receiving them.

With mutual legal assistance (MLA) CPS prosecutors’ work closely with law enforcement to issue more than 250 requests each year, but it is also possible for UK law enforcement to obtain material that will be admissible in domestic proceedings, from overseas using less formal methods.

It is important to add however, in terms of receiving or executing the over 7,000 MLA requests sent to the UK each year, the CPS has no involvement; these are handled by the Home Office and law enforcement partners.

Where multiple countries have jurisdiction to prosecute, something increasingly common in cybercrime cases and complex frauds, prosecutors are best placed in the UK to negotiate and determine the appropriate venue.

The UK is also fortunate to have a network of prosecutors deployed overseas, covering much of Europe, but also further afield in Middle East, Africa, and Americas. These prosecutors can build relationships, networks, and jointly solve problems in a way that is not practical when operating and communicating remotely. We have updated our International Strategy this year, partly but not exclusively in light of Brexit, and we intend to build our network of overseas prosecutors wherever possible, according to the demands of our international casework, and also according to our available financial resource.

There are numerous examples of where our approach has led to successful prosecution outcomes, and I would like to highlight a few examples:

- Cooperation between the UK and Pakistan can be challenging for a number of reasons. The recent extradition of Mohammed Shahid to the UK, only the second extradition from Pakistan in the last 10 years, demonstrates how things can work. Shahid murdered eight people in a petrol bomb attack on a family home in Huddersfield in the north of England, in 2002. He fled to Pakistan in 2003, but after extensive joint work between UK and Pakistan authorities, including our criminal justice advisor based in Pakistan, Shahid was surrendered to the UK last year. He was convicted and last month he was sentenced to life imprisonment.

- Another example, this time with asset recovery, is an ongoing case, where we have assisted confiscation of €1m in a UK bank account on behalf of an EU Member State. We had previously restrained the asset some years ago, and our Proceeds of Crime Division worked with our prosecutor deployed overseas to obtain further information and obtain the required confiscation order. Through extensive and multi-jurisdictional correspondence with the relevant parties the monies were then released from the bank and voluntarily paid into a Government account. The €1m has now been converted into its Sterling equivalent and once again, we are using our overseas prosecutor to facilitate the distribution of the funds in accordance with asset sharing obligations.

- We have also used international cooperation in a terrorism case in which I was the lead prosecution advocate. We prosecuted a UK national, Anis Abid Sardar, for murder and conspiracy to murder based on his involvement in the construction and deployment of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) in Iraq. These IEDs caused the death of a US soldier and injury to others. Critical battlefield evidence including recovered IEDs was provided by the US to the CPS. This cooperation and evidence helped secure a conviction and a life sentence for Sardar in 2015.

From this brief overview you will no doubt see similarities with your own systems and also a lot of differences. Overall, we recognise that that many of you will find your own legal systems have systemic and procedural differences to the UK (or a least England & Wales) model. This is likely to be replicated many times over across a number of your bilateral relationships. But we can overcome these differences through working together, and through tackling international crime together.

Broader Challenges

Different legal systems may also lead to challenges in the way we approach human rights, and more recently this has also come to include data protection. This is a practical issue for all of us when seeking and providing assistance.

Human Rights

The UK has faced these problems from both sides. As many of you know our domestic law requires, for instance, UK courts to consider the human rights conditions in the country to which an extradited person may be returned. This may lead to delay and discussion whilst these issues are, rightly, considered by the courts. Raising these issues on individual cases, particularly with trusted partners, can feel difficult sometimes. Even raising this important topic now in the abstract is uncomfortable.

Raising these questions is however, necessary if we are to have a functioning system of international cooperation that respects the human rights of everyone, including those convicted or accused of crimes. The UK is prepared to have those questions asked of our system and indeed, following recent criticism of prisons in England & Wales, we have successfully defended our prison conditions in a number of extradition cases to ensure that fugitives are brought to justice.

Data Protection

Protecting and sharing data is another issue that is growing increasingly challenging and complex.

The EU has set out a high standard of data adequacy. For the time being at least, the UK benefits from the ability to exchange data with some of our closest partners in the EU for law enforcement purposes in a relatively straightforward way. With Brexit, we may be about to experience greater challenges, that some of you may already be facing, when exchanging data with the EU.

Privacy and protecting data is hugely important, but we of course know that data protection and privacy can also be used by criminals to hide their activity and hamper investigations and prosecutions. We must all ensure that we handle, retain and share personal data appropriately, but we should not allow bureaucracy and misapplication of rules to delay or prevent lawful exchange of data.

These are difficult subjects but I hope we are able to openly discuss how we can tackle these issues in a pragmatic way to ensure that criminals are not able to use differences in legal systems, human rights, or data protection to evade justice and act with impunity.

Alternatives to Prosecution

Although we have encountered it rarely, alternatives to prosecution may also inadvertently create barriers to cooperation. This may happen where more than one country is investigating the same conduct, and one jurisdiction decides to dispose of the case, for example using some form of immunity, which prevents the other interested jurisdiction from any further prosecution. We must always be mindful of how our actions can have an impact on investigations and prosecutions outside our jurisdiction.

Making it Work

Describing these challenges, even briefly, makes international cooperation seem daunting, but we should not forget that broadly we have all made our existing systems work.

The UK system, as I have just described, has rigid elements particularly around the use of coercive powers such as search warrants and asset seizure, but is broadly flexible.

Flexibility is beneficial but can also be challenging. When it comes to cooperation, as a prosecutor unfamiliar with another country’s legal system, your main priority may be certainty, not a system with sometimes wide discretion where evidence could be obtained via multiple routes.

The UK’s experience of working on criminal justice issues within its three jurisdictions and the EU is helpful here. Harmonisation has not been required for things to work effectively within the UK, or even at an EU level. Since 1999, mutual recognition rather than harmonisation has been the cornerstone of cooperation at an EU level, aided by minimum standards and high levels of mutual trust. Although this has been tested and has come under strain recently with the criminal justice systems of many partners being robustly challenged, it has proved broadly effective. From a prosecutor’s perspective I hope the UK is able to maintain this approach as much as possible with the EU, but in practical terms leaving the EU will impact and may reduce some of the UK’s international cooperation capabilities. Clearly it is not possible to apply an EU approach to all international cooperation, but there are things we can learn from this and apply more widely.

Better legal structures may be required in some areas to ensure an effective rules-based international system (RBIS). Initiatives like the Additional Protocol to the Budapest Convention to improve access to communications data are welcomed. So too are attempts to establish standards in international cooperation, such as anti-money laundering and counter terrorism financing under the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). We must ensure any structures are flexible and can be used by a range of legal systems with different standards. Indeed there must be a careful balance between seeking adequate safeguards and not imposing standards which are unworkable for many and result in any particular tool not being used.

But, even if we get these issues right (and we must) the reality is that improved legal structures and processes will only take us so far, and these structures usually lag behind developments in criminal investigation and prosecution.

Complexity, caused by unfamiliarity or for any other reason, can be addressed by good communication between prosecuting authorities. This is in my view crucial and can address many of the challenges and issues I have raised. This is demonstrated time and again through our casework, which remains the cornerstone of the CPS international strategy. I have already provided some examples of how our overseas network has led to successful prosecution outcomes, but this is not the only way to have effective communication with prosecutors on individual cases or broader issues between countries and regions.

In practical terms effective communication includes building and using forums in which discussion and understanding of individual legal systems is shared, common problems discussed, and solutions identified.

This means direct communication between prosecutors (rather than indirectly via diplomatic channels) and seeking ways to make better use of digital working internationally.

The IAP is just one important forum in which that kind of communication can happen. There are also many international and regional organisations such as IberRed, Commonwealth Network, EJN, IOC, and many others.

I therefore hope that we can all use the next few days here in Buenos Aires to foster existing networks, build understanding of other systems, and together find ways to tackle global crime effectively.

Thank you for providing me with this opportunity to speak to you this morning. I hope you enjoy the conference and I look forward to continuing the conversation in the plenary sessions.