Independent Assessor of Complaints for the Crown Prosecution Service: Annual Report 2022-23

Contents

- Introduction: What is the IAC, what does she do and how does she work?

- The Year’s Events

- Caseload Comparisons and Performance

- Reasons for complaint and resolution

- Complainants’ Voices

- Acknowledgements

- Annex A: IAC’s Terms of Reference

Introduction: What is the IAC?

The Independent Assessor of Complaints (IAC) for the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) is completely independent of the CPS, providing an impartial service that complainants can have confidence in.

My role is to:

- Investigate service complaints about the CPS following conclusion of its internal complaints process (known as Stage 1 and Stage 2).

- Look at whether the CPS properly followed the Victims’ Code guidance on the services that must be provided to victims.

- Check that the CPS has followed its complaints procedure.

The IAC’s aim is to:

- right wrongs for complainants where possible and proportionate.

- drive improvements in the CPS to reduce the likelihood of similar service complaints arising in the future.

Anyone who has complained to the CPS and remains dissatisfied with the outcome of their service complaint at the end of Stage 2, can request to escalate the matter to the IAC for an independent review. Service complaints include, for example: the conduct of CPS staff, such as rudeness or being given incorrect information; poor communication; and service standards such as breaches of its own policy, or of the Victims’ Code.

Legal complaints – such as how the CPS applied the Code for Crown Prosecutors in deciding whether to prosecute; or decisions about witnesses to call at a trial or evidence to be relied upon – cannot be reviewed by the IAC. These are legal decisions that are rightly reserved for lawyers working for England and Wales’ independent prosecution service.

Most complaints the IAC investigates contain both service and legal elements. Sometimes the central concern for a complainant is legal, and any service element may be minor. My terms of reference allow me to reject such complaints where I am satisfied that the CPS has dealt appropriately with the service parts of the complaint, or where any service element is so minor as to be disproportionate to investigate.

Legal or Service?

Although the distinction between legal and service may not always be clear to complainants, the IAC and CPS are usually in agreement as to whether a complaint is service or legal. Very occasionally, however, there is disagreement over whether a complaint falls within my jurisdiction, or whether in considering service complaints, I have encroached into legal matters. For example, this year I reviewed a case in which I found a service failure, but the CPS argued it was a legal error.

It was the case of an innocent bystander injured during an incident that was caught on CCTV, witnessed, and admitted by the defendant (who argued he was acting in self-defence). For various reasons, the CPS offered no evidence. The victim sought compensation for financial loss, and a consolatory payment for distress. The CPS accepted that the legal decision to offer no evidence was wrong, and the reviewing lawyer had failed to follow legal guidance. The complainant was told that the complaints procedure did not allow for payments to be made for legal errors.

I noted during my investigation that the CPS considered making a goodwill payment, but as the errors identified were legal, there was no mechanism for making any payment (goodwill payments can only be made for service errors). My review found that the CPS’s principal error – the decision to offer no evidence – was indeed legal and beyond my jurisdiction. I found, however, that not following legal guidance was a service failure in this case. The guidance stated that applications to stay proceedings for an abuse of process (as had happened in this case) should be brought to the attention of the Chief Crown Prosecutor (CCP) or another senior lawyer, but had not been. It was not a legal decision not to bring the matter to the attention of the CCP; rather, it was an omission. The lawyer had either not realised this was required, or had forgotten to do it. Either way, the administrative failure to follow a procedure was a service error, and I recommended a consolatory payment.

Terms of Reference

My terms of reference (ToR) set out how I work, my relationship with the CPS, and the limits of my jurisdiction. They are reviewed by me annually, and any proposals are brought to the independent CPS Board for approval. Last year I reported that the CPS reviewed my ToR without even informing me until after the proposed changes had been drawn up.

I raised my concerns about this, and the need to safeguard my independence, with the CPS Board. I was pleased that they recognised my concerns, took the view that the revised ToR would need further work to ensure the independence of the IAC, requested that further discussions between the IAC and Private Office should take place, and stressed that the IAC should lead on amending the ToR. It was agreed that a revised ToR should go back to the Board for agreement, which happened in November 2022.

As the Board did not sign off the ToR, no changes were made last year. Working with Private Office, a number of amendments were agreed and the Board sought assurance that I was content with them before they were approved. The updated version was published on the CPS website in January 2023 and a further revision to include referrals to civil litigation (see elsewhere in this report) was published in May 2023.

You can find the updated IAC’s terms of reference (ToR) at the end of this report.

Moi Ali

May 2023

The Year’s Events

As ever, this has been a busy year – both in terms of complaints reviews, but also in non-casework related work as set out below.

Consolatory Payment Guidance

Following an investigation in August 2019, I recommended that the CPS look at a system of “payments to put things right” – which would include “consolatory” (payments for distress) and “compensatory” payments (payments for actual financial loss), but without the distinction. The emphasis was to be on when a payment may be a suitable remedy.

The review of the existing consolatory payment guidance started in 2020, but was paused and I did not see a draft until summer 2022. I was pleased it acknowledged the PHSO’s guidance that financial compensation ought to be considered for financial loss, but disappointed that the draft went on to suggest that removing the suggestion of compensation and links with loss would enable it to comply with the “spirit” of the PHSO’s guidance without actually complying with it.

In practice, the revised guidance continued to differentiate between consolatory and compensatory payments, and added further confusion by stating that while consolatory payments could be made for distress caused by service failure where there had been financial or material loss, it could not be used to compensate for loss and must not be linked to loss – even though payment would be calculated using documentation supplied by a complainant evidencing financial loss! Far from making matters clearer, this seemed to be making it more complex.

While I note that it was internal guidance rather than an external published document, I was concerned that its laudable attempt at consistency by putting an indicative amount or sum alongside service failures such as Victims’ Code breaches, came across as cold and lacking in an understanding of the impact on victims of service errors. For example, it was suggested that not bringing a Victim Personal Statement (VPS) to the attention of the court should attract a goodwill payment of just £100. Victims have told me that their desire to read their VPS was about being able to explain the impact of a crime on them, so they could draw a line under devastating events and move on with their lives. The impact of being denied that opportunity stays with victims forever, as they never get that closure they so need.

The draft talked of the failure to request a restraining order causing “inconvenience” – in the cases I have seen, it causes genuine fears for safety, anxiety and worry. The guidance suggested complainants could receive a goodwill payment for distress in such circumstances, but not reimbursement for the costs of having to privately seek protection themselves through the courts following a CPS service error.

This document appeared to me to take an approach based on avoiding liability rather than righting wrongs. A new element of the policy was ensuring that any payments were “exceptional”. It took the view that even in cases where professional lawyers had admitted a legal error which had directly resulted in a case stopping and a victim being denied justice, an admission of fault and an apology should suffice. There should be no consolatory payment, as such payments could be an admission of liability. In such cases, a victim would not only have the denial of justice to contend with, and the complaints process to navigate; they would then have the double injustice of having to engage a lawyer, and embark on the costly, time-consuming and stressful civil litigation route to secure any payment whatsoever, however small. I was unwilling to back these proposals, which did not appear to have fairness for the victim at the centre.

The draft guidance underwent a number of revisions based on my feedback, and the CPS accepted my suggestion to consult the PHSO on the final draft. I met with the Head of Civil Litigation, as I remained concerned that people who complained about financial loss using the complaints process, and who had voiced absolutely no desire to litigate, were being given civil litigation as the only recourse. This seemed to me to be a further injustice, on top of the original CPS error.

Although I remain unhappy with the eventual outcome, as the revised ‘Goodwill Payments Guidance’ published in May continues to differentiate between consolatory and compensatory payments, rather than taking an approach aimed at putting things right, progress has been made.

Although it is not a solution, I am heartened that it has been agreed that the IAC can make an “IAC referral” to the Civil Litigation (CL) Team where I believe that compensation should be paid. The CL Team will look at IAC referrals and treat them in a similar way to a ‘letter before claim’. The effect of this will be that a complainant does not need to go to the trouble and expense of engaging a solicitor. The CL Team will consider the matter on its merits and respond directly to the complainant with either a no-fault offer, or with reasons why no payment will be made. The CL Team will meet with the IAC to discuss the outcome of a referred case, and report annually on the number of cases where the CL Team made a “non-confidential” settlement to an individual following an IAC referral.

Both the IAC and the CL Team will explain to the complainant in their final letter that the complainant can still take legal action if they wish. A referral to CL will not delay the dispatch of the IAC’s final determination or the payment of any recommended consolatory/goodwill payment.

The revised guidance and the IAC’s ToR have been amended to make reference to this potential remedy and were published in May. Although the guidance is still not what I would have liked to have seen, many of my concerns have been taken on board.

HMCPSI

I met with His Majesty’s CPS Inspectorate (HMCPSI) during its thematic inspection on the Crown Prosecution Service’s handling of complaints. This inspection was a follow up to HMCPSI’s inspection into Victim Liaison Units, but the focus this time was solely on the feedback and complaints policy. They wished to discuss my view of the letters at Stage one and Stage two of the complaints process, and any issues or improvements I had observed. The aim of the inspection was to examine the quality and timeliness of CPS letters in response to complaints received. The report is due to be published in July.

The Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman

The ‘Stage 3’ independent IAC report is the end of the complaints process, except in cases that qualify for escalation to the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (PHSO) via a Member of Parliament. During the year, it was brought to my attention that the wording on the PHSO’s website in relation to the CPS was unclear. It appeared to imply that victims could escalate any complaint to the Ombudsman. That is not the case. Victims can complain to the CPS and escalate service elements to the IAC, and can then raise breaches of the Victims’ Code with the PHSO if they remain dissatisfied. The Ombudsman can consider only the parts of the complaint relating to the Victims’ Code breach. (Defendants can complain to the CPS and escalate service elements to the IAC, but as defendants are by definition not victims, they cannot escalate to the PHSO.) Following a discussion with the PHSO, their website has been updated to clarify that only breaches of the Victims’ Code can be escalated to the Ombudsman.

Mr B’s case

I reported last year on two escalations to the PHSO. The case of Mr B was closed in 2020/21, escalated to the PHSO in 2021/22, and was still ongoing at the time of writing. Mr B was the victim of a violent, unprovoked racially aggravated assault in which he sustained serious injuries requiring major surgery. I will report on the outcome of that case in next year’s report.

Follow-up correspondence I had with Mr B caused me to question how the IAC gets assurance that recommendations are fully implemented (not all my recommendations in the case of Mr B had been). My office keeps a list of all open recommendations, and we used to close them when the CPS confirmed that they had been completed. Following Mr B’s case, this year I introduced a strengthened process whereby my office now requires evidence that a recommendation has been completed. For example, if there is a recommendation to arrange training, my office seeks information about the date it took place, the content, and the attendees, rather than simply accepting that it has happened. I also now ensure that a copy of any apology or further reply is provided for our records, and I personally check that it accords with the spirit of any recommendation.

Mr A’s case

Mr A’s case concluded with the PHSO in May 2022. He was seriously injured in a road rage incident. The defendant was initially charged with grievous bodily harm with intent, and later an alternative (lesser) charge of causing serious injury by dangerous driving was added. No one explained this to the victim, and the defendant was convicted on the lesser charge.

I recommended a consolatory payment as Mr A had been caused avoidable distress, there had been a breach of the Victims’ Code, and he had been left without a proper understanding of what had happened in court as no one explained the purpose of adding an alternative charge.

Mr A purchased a transcript from the court to help him understand the outcome of the trial, and he wanted the CPS to reimburse him the cost of this. In cases where a victim has not been notified of a trial date, I have asked the CPS to pay for a transcript to enable the victim to understand what happened at court. In this case, however, the victim was present throughout proceedings. I concluded on this point that Mr A could have gained an understanding of the outcome simply by writing to the CPS to seek a proper explanation, without the need to purchase the transcript.

It transpired that Mr A had suffered a serious head injury during the incident, which left him cognitively impaired. The PHSO determined that the CPS should reimburse Mr A the full cost of the transcript, and this has now been paid.

PHSO referrals in 2022/23

This year the PHSO received 16 complaints about the CPS, but it is unclear how many of those had first been escalated to the IAC. Of the 16, 15 were concluded without a full investigation, and one was accepted and is currently under investigation. As far as we know, it was from a complainant whose case was not accepted for investigation, as it did not fall within the IAC’s jurisdiction.

Engagement with the PHSO

The PHSO is hoping to establish an independent tier organisations’ network, and I have engaged alongside counterparts in various government departments and arms’ length bodies on how to take this forward. Being an independent adjudicator can be an isolated role, and having a network of others in similar roles with whom best practice can be shared, would be valuable.

The PHSO has also brought together independent complaints adjudicators to discuss how we might use the new UK Central Government Complaint Standards when scrutinising responses from the organisations we oversee; seek our views on the role and responsibility of the independent tier under the new Complaint Standards; and discuss whether there would be a benefit in creating a ‘Model Procedure’ for the independent tier to help drive a more consistent approach to complaint handling across government.

Feedback

For almost a decade, the IAC was “the guardian” of the CPS complaints and feedback process, and this term formed part of the IAC’s terms of reference until November 2022. During the year, and prior to my ToR changing, I reviewed a case which highlighted my guardianship role in respect of feedback.

Mr C complained to me about how his feedback was handled. He had written to the CPS raising concerns about the handling of a domestic violence case reported in a specialist publication, which I shall call the ‘case of D’, in which a Court of Appeal judge criticised the CPS for undercharging the defendant. Mr C was concerned about the role of CPS Direct (the CPS’s ‘out of hours’ charging service), and queried why no one at CPS Area level had spotted an error by CPS Direct and remedied it. As he was not a party to that case, his correspondence was rightly treated as feedback. (The CPS Feedback and Complaints Policy states that third party correspondence unconnected to a case cannot be responded to as a complaint.) He was told that the CPS takes cases of domestic abuse seriously and aims to deliver justice and provide protection to such victims.

He wrote again expressing dissatisfaction with the response; complaining about its brevity and content; and questioning why the continuing duty to review did not happen in this case. He asked for the matter to be treated as a service complaint. He also sought to find out, using Freedom of Information (FoI), what actions the CPS had taken as a result of the judge’s remarks.

The Stage 1 response stated that as Mr C had no direct involvement in the case, he had no right to a detailed reply: “We are unable to provide you with further details of this within the remit of our Feedback and Complaints’ Policy which is why this was not addressed further in the response. I hope that this clarifies the brevity of the response that you received.”

Mr C wrote again, requesting escalation to Stage 2 and enquiring about whether the CPS has an adequate system of reviewing clearly erroneous decisions made by CPS Direct when a file arrives with the CPS Area. He explained that he was concerned with the principle, not the specific case. The Stage 2 response said the CPS could not provide details of the handling of the case of D.

Mr C complained to me that the CPS had missed the point of his complaint, which was not the specific prosecution of this case; rather, the CPS had made an egregious mistake, as highlighted by the judge in the case of D, and he believed that the system of review was defective and should be put right. He was unhappy with the CPS’s comment about reviewing processes to ensure that errors of this sort are rectified in future, as it had been over two months since the case of D and the review should have been completed. He stated that replies had been patronising and bland.

I agreed that the responses were uninformative, bland, and generic. The CPS had written to Mr C: “Please be assured that the Crown Prosecution Service takes cases of domestic abuse extremely seriously. We are determined to do all we can to deliver justice for all and to provide victims with the greatest possible protection from repeat offending.” The CPS could have addressed the wider issues raised – such as the role of CPS Direct in charging, or how Area-level reviews detect and rectify undercharging – all without revealing case-specific information. Such a reply may have provided Mr C with the assurance he sought, and as he indicated, would have brought the matter to a close.

The CPS’s feedback procedure states that: “Where it is possible and appropriate to do so, a response to feedback will be provided.” I agree that there are circumstances where no tailored response to feedback is necessary. Organisations with high volumes of correspondence on an issue sometimes send standard responses (for example, in response to feedback on a particularly high-profile case reported in the mass media, where members of the public are expressing general concern but are not asking specific questions about process). There is no problem per se in issuing a standard response, so long as it addresses in broad terms the issues raised.

The CPS Area in question argued that the policy did not require a detailed reply, and that is why Mr C was sent a brief response. I disagreed, as the policy does not prevent a detailed response from being given, and should not be used as an excuse to send short, generic replies that leave correspondents feeling fobbed off. Mr C raised legitimate public interest concerns of a public authority. Citizens should be able to make such enquiries, and public bodies should be accountable and transparent by providing appropriate explanations. The CPS is accountable to the public in many ways already, and accountability to the public via a complaints and feedback policy is another way of building public trust and confidence, and the feedback mechanism should not just be one-way.

Concerningly, the policy as worded allows the CPS to provide no reply whatsoever (not even a brief or standard one) to members of the public who have gone to the trouble of writing to share their views or experiences: the words “possible” and “appropriate” could be used to justify not sending a response at all. The CPS states in the policy that it encourages feedback, but boilerplate replies (or a lack of response) deter citizens from raising concerns of public interest, deny the CPS valuable feedback, and create public mistrust. I welcome the CPS’s ongoing review of guidance on the feedback policy.

There is no point in encouraging people to provide feedback if nothing is done with what is said. The published Feedback and Complaints document states that feedback will be recorded and “analysed in order to help us [the CPS] to continue to deliver a high standard of service to the public” and “We are committed to delivering excellent service standards and will use feedback to identify and develop good practice.” Following this complaint, I met with the CPS to discuss this, and I asked to see the analysis for the previous two years to understand how feedback has helped shape better practice and organisational learning and improvement. Having not received this, I chased up the matter and learned that there is no systematic capture of the analysis of feedback, and nor does anyone capture whether anything has been done as a result (either locally, or in terms on wider organisational policy making).

The CPS has agreed that the policy needs to be reconsidered, given that as drafted, it creates a misleading expectation about how feedback is considered and used. I will be meeting with the CPS in the coming year to discuss how the definition of feedback can be sharpened, so that it becomes a tool for capturing and actioning useful feedback. There is also an accepted need to be more open and honest with the public on how feedback (and other non-complaint correspondence) will be treated. It is disappointing that feedback has not been captured to date, but the fresh look at feedback and how it is used is welcome.

As a result of this complaint, I was informed that feedback cases are looked at to determine whether they should in fact have gone down the complaints route instead (with, in the case of service complaints, potential access to an IAC review at the end). In June 2022 I asked for this data to be shared with me quarterly, as I intended to report the statistics in this annual report. When I chased the matter, I was told that it did not exist. I have raised this with the CPS and we will discuss it further when we meet to look at feedback more generally.

Visits

Visits to CPS area offices have resumed. During the year I visited Cardiff and Leeds in person, and Wessex virtually – and I attended the CPS Senior Leadership event in Bristol. I intend to visit different Areas this coming year, to run discussions on improving complaints handling.

Case complexity and follow-up

For the third year in a row, case complexity and follow-up correspondence has adversely affected turnaround times, as has the continued use of large electronic case files containing documents embedded within documents. I had hoped for a return to paper files, but as the return to the office was not completed during the year, this did not happen.

Background Notes

The CPS is required to provide a background note detailing the history of a case and all relevant information. Despite again updating the template I produced previously, to help ensure that I receive all the information I need for my investigation, the quality of what I get back remains variable. I have continued providing feedback to the CPS on particularly good (and particularly bad) examples, and explaining why some briefings have fallen short of my requirements.

IAC on the Move Again

Last year I reported on a difficult year following the move from Communications to Operations. It was a good idea to locate the IAC in an area where operational improvements identified during reviews could be implemented quickly, but in practice it did not work, and relationships were strained. In September 2022 the move of the IAC function to sit within Private Office to act as a further safeguard on IAC independence has been positive.

Caseload Comparisons and Performance

Complaints received

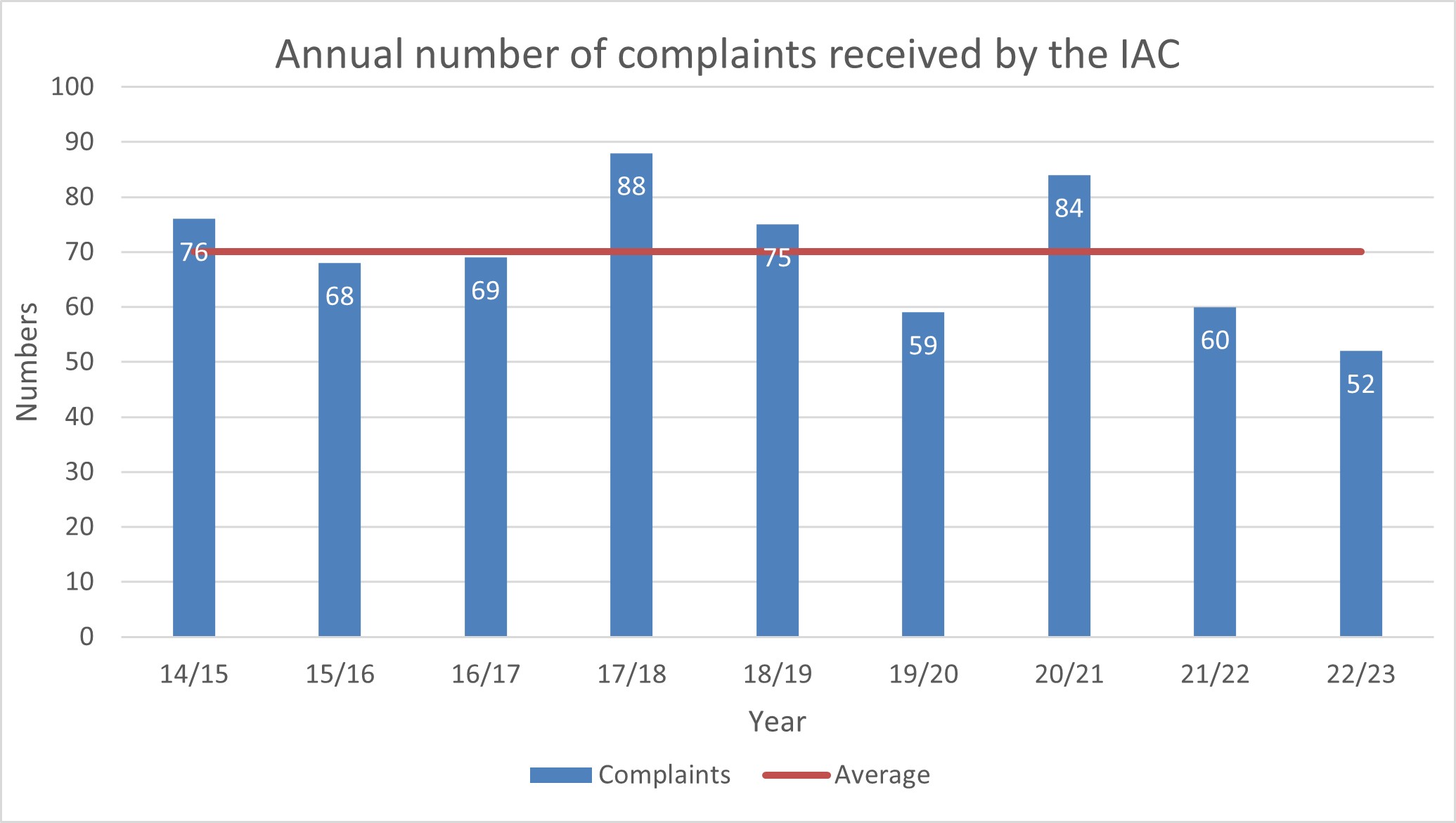

The number of complaints received by the IAC’s office has fallen again, from 84 in 2020/21, to 60 in 2021/22, to an all-time low of 52 this financial year – although this may simply be part of the normal year-on-year fluctuation rather than a trend. In line with the fall in the number of cases escalated to my office, 36 cases have been accepted this year (41 last year). Of these, 24 have been completed and dispatched; 10 have been assessed, the file has been prepared, and they await review; and at year end, two were being reviewed by the IAC.

In addition, there were three cases on hold and four awaiting assessments. A further seven were rejected and two withdrawn (see below).

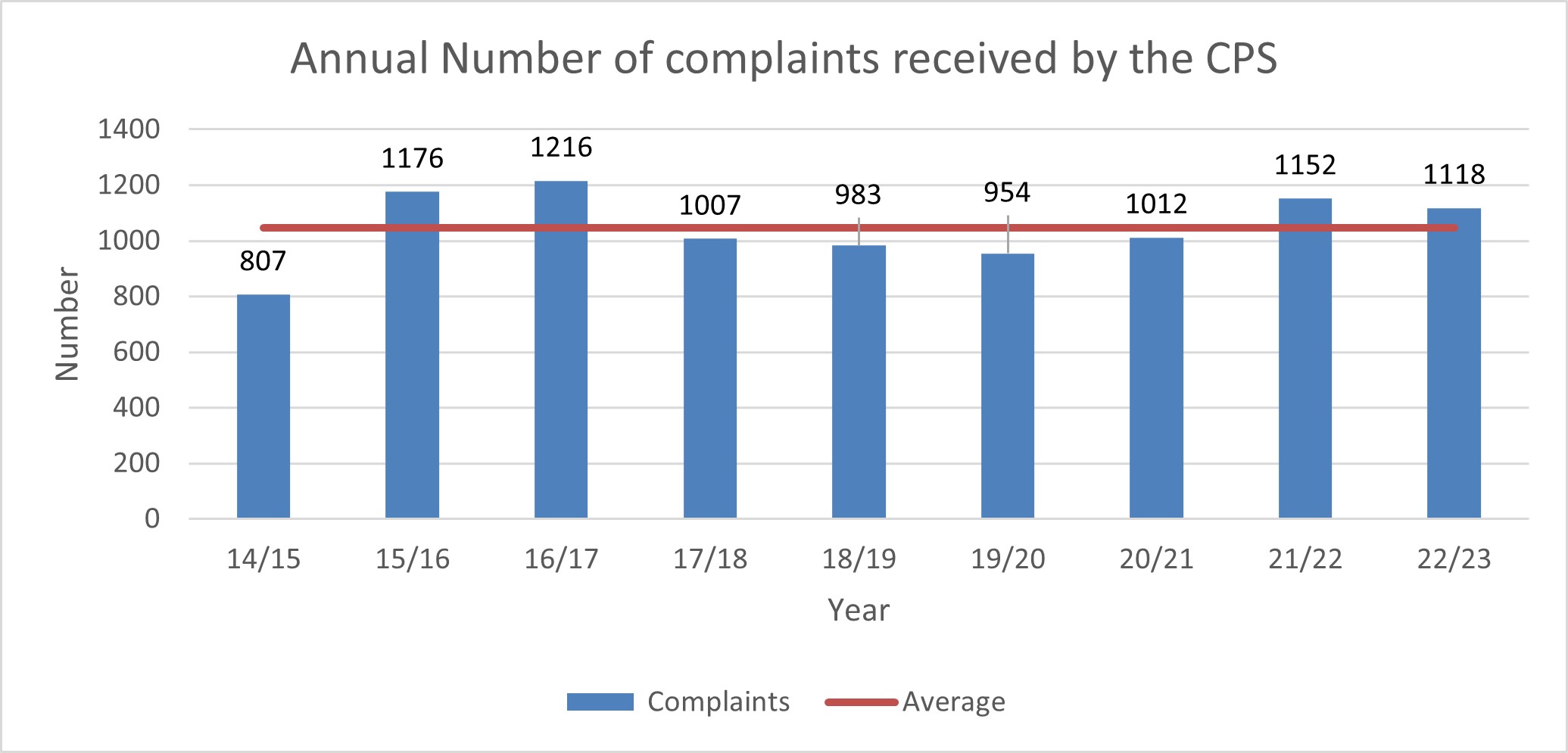

The CPS complaints data below shows the number of complaints received by the CPS.

Complaints rejected

There has also been a marked decrease in the number of complaints the IAC has rejected this year (8 in 2022/23,19 in 2021/22). One of the eight cases was received in March 2022, but rejected this financial year.

The reasons for rejection were:

- Six were primarily concerned with legal matters so were rejected as not falling within the IAC’s remit (it was 14 cases last year)

- One case was rejected for reasons of proportionality, in line with my terms of reference. It involved a complainant who was considering civil action against the CPS, and raised concerns that the CPS was not assisting and not allowing access to the complaint process. The IAC found that the matter did not fall under the complaints policy, and although arguably there were potential service elements the complainant could complain about, such as the slowness of replies to his requests, I found that these were not matters that could be considered proportionate to investigate at the independent review stage.

- One complaint was rejected as not concerning the CPS, although it was a very sad case and therefore received a personalised reply from the IAC (in total, two rejected cases received personal replies from me. This usually happens when the victim has been through an ordeal with the criminal justice system and feels traumatised, or that they have not been listened to. Where possible, they are signposted to other appropriate agencies)

- Additionally, two cases were withdrawn (although one came back the next financial year and her complaint was reviewed).

Accepted, completed or ongoing during 2022/23

Of the 36 complaints accepted by my office as falling within my remit between 1 April 2022 and 31 March 2023:

24 were completed and dispatched

One was in final draft stages awaiting last checks.

One was awaiting a draft.

10 had completed formal assessment and were accepted as valid for an independent review, but had not as yet been formally accepted by the IAC. (Those will be carried into 2022/23. This is a significant drop on the 24 carried over last year.)

This year I also completed 10 complaints received prior to 1 April 2022 (carried over from the previous year). Of these, two were not upheld, six were part upheld and two were fully upheld.

Overall, fewer cases were completed this year than in 2021/22 (34 this year compared with 51 last year). This was in part due to spending time on other work (such as the Terms of Reference review, the Consolatory Payments Guidance review, and time out at the Senior Leaders’ event), and in part due to working fewer days this year. Although the IAC’s number of contracted days has been increased this year from 48 days to 60, the IAC (and her predecessor) has for some years worked more than the allocated time and the CPS has always funded additional days. This year the IAC has worked only the contracted days, and no additional days. Even with the increase, this has resulted in slightly fewer days than in previous years.

Performance and waiting times

With one exception, every case closed in 2022-23 was completed within the 40 working day target, when calculated according to the previous method. (Since the establishment of the IAC’s office, the clock has started only when a complaint is formally accepted by the IAC.) The overdue case was the result of extended discussions with the CPS about a recommendation that was rejected (more on that elsewhere).

As I have pointed out previously, this is a disingenuous measurement because it does not reflect actual waiting times. The clock ought to start as soon as the files are ready for the IAC, not at the point at which the IAC requests them. To provide greater transparency, I committed to reporting actual waiting times (how long complainants wait from the date the case file is ready). Here, for the first time since the IAC office was established in 2013, is data that more accurately captures wait times. The average wait is 65 working days, a good deal longer than the target 40 days. It masks great variety, however, as seen below.

- Seven cases were completed within the 40-day target, using the real measure.

- The shortest wait from the file being ready for the IAC, to a case being completed by the IAC was just one day, and the next shortest was two days.

- The longest wait was 106 days.

To stress, complainants are not waiting longer this year than in previous years; rather, the actual waiting time is now being presented in a more transparent way.

The 40 working days target is, and for many years has been, unrealistic for a service that operates just 60 days a year, and has always had a backlog. The IAC target is lower than many other independent adjudicators. Some provide no target time (such as the Independent Adjudicator for Higher Education, which aims to conclude adjudications “as quickly as we can. But some complaints can take several months…”). The Department for Work and Pensions independent examiner allows 20 weeks from a complaint being allocated to an investigator. I intend to discuss reviewing targets for the coming year so that complainants have a more realistic indication of when they can expect a final response.

Who complained?

Of the cases completed in 2022/23, 26 complainants were victims or the relatives or representatives of victims, and six were defendants or those who had been considered for prosecution (down from 19 last year). Two complainants were not directly involved in a case, but had complained about how their enquiries (one case specific, one not) had been handled.

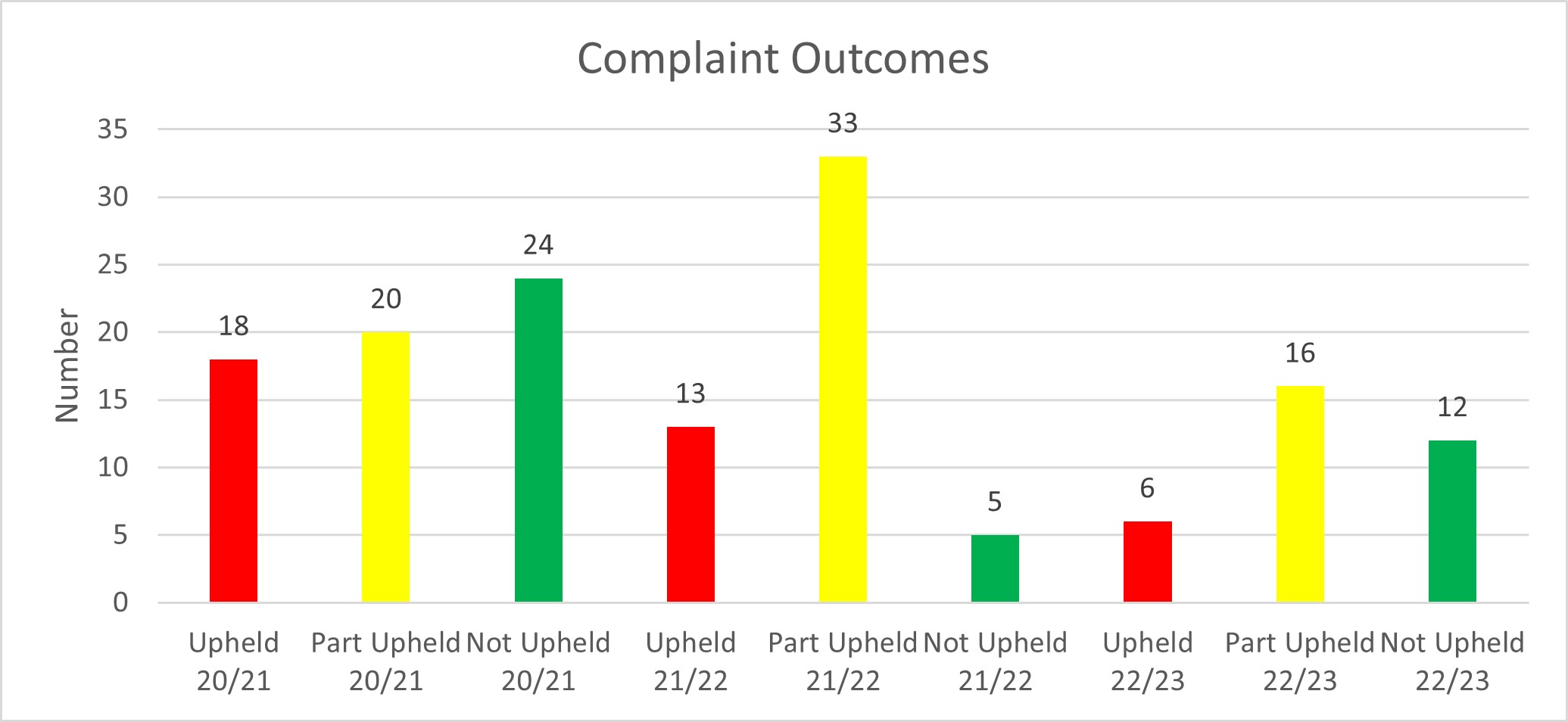

Outcomes

The table below shows the outcome of my reviews: although the majority were either wholly or partly upheld (22 cases, down from 46 last year), the number of cases not upheld has increased to 12 (up from just 5 last year, from a bigger case load). This again adds weight to better handling at Stages 1 and 2.

Recommendations

I made recommendations in 14 cases (some cases contained multiple recommendations), and all 14 involved some sort of payment, and in two of the cases I asked the CPS to provide further information or an explanation to the complainant.

Where the CPS does not accept a recommendation, it must be reported to the CPS Board. For the first time ever, the CPS rejected a recommendation this year. The circumstances were similar to a previous case where the recommendations were accepted. This year’s case related to a victim whose car was deliberately damaged. The defendant was found guilty in his absence, and a warrant was issued for his arrest. He was sentenced in a different court, where the CPS forgot to ask for compensation to cover the £1,000+ damage to the car, for which the victim (Ms E) had completed police paperwork and provided receipts.

Ms E complained to the CPS, who admitted that her financial losses “were not considered by the prosecutor at court”. She escalated her concerns, stating that it was “not right or fair that because the prosecutor failed to draw the court’s attention to the compensation application that I should suffer a financial loss”.

The Stage 2 response stated: “… the court did not make any order for the defendant to pay you compensation to cover the cost of repairs to your vehicle. The police had provided details of the cost incurred to repair your vehicle but the prosecutor at court… did not make a specific application for you to be reimbursed… the court does have the power, considering the facts of the case, to make an award for compensation without an application being made by the CPS but nevertheless the prosecutor should have drawn the court’s attention to your loss… I am grateful to you for bringing this matter to my attention and wish to reassure you that providing a quality service to victims is a priority for the CPS. As the case has concluded, we are unable to reopen the case in order to request compensation on your behalf…” This was a very roundabout way of admitting an error, without using the words ‘error’ or ‘mistake’.

Ms E was told her complaint was legal and could not be escalated to the IAC, but nonetheless she escalated it to me and I found it to be a very clear service complaint.

The defendant caused the damage, and it was right that he should be asked to pick up the bill. An award of compensation by the court is not guaranteed (payments depend on many factors, including the defendant’s ability to pay) and had the court rejected the claim, that would have been the end of the matter as far as I was concerned.

The problem is that through a CPS omission, the court was never asked to consider the matter. For this reason, I recommended that the CPS should pay compensation to cover the cost of the car repairs. Although the defendant’s actions caused the damage, the CPS’s inaction denied Ms E the opportunity to attempt to recoup repair costs. Ms E will never know whether she would have been awarded all, or nothing – or only a proportion of her losses.

Ms E said the judge asked whether she had claimed on insurance, and also about costs and receipts. In a meeting, the CPS told me that despite knowing that she had not made an insurance claim, the judge still chose not to award compensation – but that later proved to be incorrect. That judge did not sentence the defendant. He was sentenced the following year in a different court by magistrates, for this and various other offences. It was at this point that the CPS made the error. It is possible that the original judge was considering awarding compensation. Unfortunately, the CPS did not bring the request for compensation to the attention of magistrates at the sentencing hearing.

Under the heading “Remedies and Compensation”, my terms of reference allow me to recommend remedies. Compensation is not specifically mentioned (other than in the heading), but the list is not exhaustive. Ms E provided clear evidence of actual financial loss (as a result of the defendant’s actions) and she may have suffered financial loss due to the CPS failure to ask magistrates to consider making him repay the repair bill.

No one knows whether compensation would have been awarded. I note the CPS argument that the judge, who was aware of her losses, could have made an award without being asked, but the judge did not sentence the defendant – and it is at sentencing that matters of compensation are considered. Magistrates could have awarded compensation of their own volition, but the prosecutor did not bring Ms E’s losses to their attention. Some culpability lies with the CPS.

The CPS Prosecutors' Pledge promises that on conviction, a prosecutor will “apply for appropriate order for compensation…” I found the CPS to be in breach of its own pledge, and considered it reasonable that the CPS should pay for its mistake, rather than expect the innocent victim to pick up the tab. Ms E completed all the necessary paperwork for compensation and provided receipts for the work. She did everything required, and the CPS let her down.

The CPS complaints policy “should not be used to allow complainants to avoid making a claim against their insurance when a suitable insurance policy is in place and any payment will be limited to the policy excess, unless there are exceptional circumstances.” So Ms E could have claimed on her car insurance, and sought a refund of the excess from the CPS, but there was no guarantee the CPS would pay. It was a risk, especially as the CPS had not offered to pay the excess, or even to consider paying it.

Furthermore, even if the CPS had paid the excess, Ms E might still be out of pocket. That is because in the absence of ‘no claims’ protection insurance, victims potentially face uninsured losses such as losing no claims bonuses, and/or facing inflated premiums in subsequent years. In those circumstances, arguably, victims face uninsured financial detriment over and above any policy excess.

This complaint was particularly frustrating, as I have raised the failure to seek compensation from the courts multiple times with the CPS, including writing to CPS centrally to ask for this to be addressed by way of a checklist or some other mechanism that would ensure that it does not happen again. It is disappointing that I am still seeing cases like this.

A similar case in 2021, in which the CPS accepted a recommendation to make a payment, also involved external counsel failing to seek compensation from the courts. The CPS argued that the guidance is to compensate for uninsured loss, but the complainant was insured (but did not want to pay the excess). The CPS agreed to consider (but not guarantee) reimbursing him for his excess, but his primary concern was that his premiums in future years would increase following a claim. This would have led to two uninsured financial losses: an excess charge (that the CPS may, or may not, repay) and a likely premium increase in future years (which he would have to shoulder). All the financial risk lay with the innocent complainant.

The CPS could have put this right. A consolatory payment could have been made for distress caused by the CPS’s accepted service failure that had caused financial loss and resultant distress. Equally, a compensation payment could have been made for uninsured financial loss as outlined above. I recommended a consolatory payment in this case for distress caused by the CPS failure to seek compensation from the defendant, and the distress of having to face future inflated premiums.

As Ms E’s case illustrates, yet again the failure to seek compensation for victims of crime remains a feature this year. I cannot understand why it has not been addressed, as it causes significant distress and financial hardship to victims. I have been raising this year-on-year, as did my predecessor before me.

Reasons for complaint and resolution

The other consistent themes remain:

- Administrative errors: such as the wrong date for a court hearing being provided to a witness, or a document being placed in the wrong file.

- Case management: there have been cases which were not actively managed, such as when the CPS has not chased the police for overdue or missing information, or failed to escalate within the police when action plans became overdue. This can result in the discontinuance of a trial.

- Last minute review/preparation: this remains central to many complaints. In these complaints, case files are often reviewed too close to the court date, typically the day before, when it can be too late to secure missing information. This may mean that a trial has to be adjourned, or a prosecution dropped altogether, leaving victims feeling that justice has not been done.

- Agent prosecutors: they continue to feature in complaints cases. Perhaps because they are external to the CPS, they are less familiar with its policies (despite receiving training).

- Victim Personal Statements (VPSs): the failure to offer the victim an opportunity to read out their VPS is not only a breach of the Victims’ Code: it causes distress to those wanting the defendant and the court to understand how they have been affected by a crime. This can be very cathartic for victims, and some believe that the outcome would have been different if only the court had understood the full impact of the crime on them.

- Missing, incomplete or inadequate Hearing Record Sheets (HRSs): the HRS is the CPS’s record of what happened at court. It is a vital document if there is a complaint. Sometimes the HRS is missing, or lacking in sufficient detail. For example, it does not always record whether compensation was asked for; what the reasons were for magistrates refusing an adjournment; or what instructions were given in phone calls to the CPS.

- Behaviour at court: Sometimes victims complain about poor communication at court, insufficient time with prosecution counsel, or insensitivity and brusqueness (often involving agent prosecutors).

Consolatory payments

Complainants often seek a consolatory or ‘goodwill’ payment (a payment to make amends for stress, distress or hurt caused by service failures or maladministration). In line with HM Treasury guidance, consolatory payments from the public purse must be modest – usually no more than £500. The IAC can recommend that the CPS makes a consolatory payment in circumstances where an apology and explanation do not represent sufficient redress.

In the cases closed during 2022-23, I recommended 14 payments. The lowest was just £100, although this was on top of the £400 the CPS had already offered, bringing it up to the maximum consolatory payment of £500. (Sometimes, as in that case, a consolatory payment has already been offered and accepted before a case reaches the IAC. Unless the amount is so low as to be unreasonable, the IAC will not substitute a larger sum.) The highest payment was £500, and the total came to £7,050 (compared with £4,300 last year; £6,633 in 2020/21; £4,550 in 2019/20; £2,600 in 2018/19; and £3,470 in 2017-18). This year’s figures are slightly skewed by one single complaint involving six individuals.

Complainants’ Voices

By definition, a complainant is unhappy – that is why they are complaining. By the time they reach me, having already negotiated two stages of the CPS complaints process, they are often extremely unhappy. Often a complainant takes comfort from having an independent person understand why they are dissatisfied, even if the complaint is not upheld or is only partly upheld, as in this case:

“Please pass on my sincere thanks to Moi Ali for her very comprehensive and sympathetic letter. I am very grateful to her, and I very much appreciate her compassion and understanding regarding my case. I am still truly heartbroken about what has happened, but her kindness and understanding has at least been of some assistance to me in coping with the situation.”

My determinations tend to be quite long, as they go into a lot of detail. I have found that complainants find this reassuring. It shows that I have spent time getting to understand the issues, as these quotes three show:

“Thank you for your letter of [date]. I find it both thorough and thoughtful and am grateful for your time.”

“Thank you for the in-depth letter you sent to me it is appreciated. I have spoken to my Mother and she is grateful for your… effort to deal with the complaint.”

“Thank you for your time in reviewing and upholding the complaint my colleagues and I submitted and for the feedback you provided [name], it is much appreciated.”

The importance of being listened to is a theme that emerges in feedback my office receives, as these quotes show:

“Can you please thank Ms Ali for her comprehensive review of my complaints against the CPS.

"It is the first time I have felt that my complaints have been listened to, rather than being issued a template letter with corporate jargon to placate an individual.

"Her comments have made me feel as though I am a person again, with personal issues and personal concerns rather than just another generic victim. It is much appreciated.

"I am also grateful that her comments and findings are issued to the Director of Public Prosecutions, the CPS Chief Executive and the Chief Crown Prosecutor for [CPS Area]. I am hoping that the comments and findings are acted upon by these, so that future victims do not have to experience what I endured or to have similar levels of tenacity to seek justice for crimes committed against them… Thanks again to Ms Ali and her team.”

“Thank you for your detailed reply. I am grateful you agreed to review my concerns and encouraged that you have contacted relevant parties to improve service provision in an attempt that others will not be in the position I was going forward.

"Whilst the offer of a financial compensation was completely unexpected, I will humbly accept your offer and consider how to put this to good use.

"Finally, my sincere thanks and appreciation for the time, effort and genuine understanding taken by your organisation. You listened and understood. Over 3 years since this dreadful experience began, you gave me a voice.”

The above complainant had not sought a goodwill payment, but the mistakes made in her case were such that it was a necessary. Another victim asked for her payment to go to a charity, but as this was not possible, she wrote:

“Thank you for the Good will payment, being able to donate this to Women's Aid means a lot to me personally and will be invaluable for other women and children supported by his charity as well.”

Many people pursue their complaints to make the service better for those who come after them, as some of the above, and this comment below, shows:

“Thank you for this very detailed response - I really appreciate it. We have had abject apologies already from CPS, but to actually hear that an independent body considers that we have been denied justice - and indeed will never have it - comes as something of a relief. I hope that the changes to process will stop something like this ever happening to anyone else.”

My assistant also receives many compliments for his kindness in dealing with people who contact the office. The human touch makes a significant impact on people who have been through a difficult ordeal, and we must never forget the person behind the complaint.

Moi Ali

Independent Assessors of Complaints

May 2023

Acknowledgements

My thanks go to Max Hill KC, the Director of Public Prosecutions, for reading every report I write. That level of interest at the most senior level is valued, and is a demonstration that the work of the IAC is seen as important within the CPS. The CPS Board of non-executives has also shown a genuine interest in my work, and this report is presented to them as a separate agenda item.

At a personal level I am always grateful to my assistant, Tony Pates, for being the interface between me and the CPS – preparing files, chasing up information, and managing follow-up queries, as well as liaising directly with complainants. He always does so calmly and patiently, and although employed by the CPS, recognises and understands the need for an independent IAC. Immense thanks also to Mercy Kettle, for supporting the IAC office in so many ways.

Grateful thanks to Harvey Palmer in Private Office for ensuring that the IAC is consulted as appropriate and provided with sufficient support and resources.

Finally, I would like to thank CPS Areas for their support in enabling me to undertake investigations into their work.

Moi Ali

May 2023

Annex: IAC’s Terms of Reference

1. Introduction

1.1. The Independent Assessor of Complaints for the CPS (IAC) reviews complaints about the CPS’s quality of service; checks that the CPS has followed its published complaints procedure; and can review complaints aspects of the Victims' Code.

2. Role and Remit

2.1. The IAC considers service complaints at Stage 3 of the CPS Feedback and Complaints procedure. Service complaints are those relating to the service standards and conduct of CPS staff. Examples include being treated rudely or unfairly by staff members, failure to provide the correct information, or unnecessary delays in either the service provided or in responding to complaints.

2.2. The IAC cannot review legal complaints, such as those solely about prosecution decisions. Victims who wish to request a review of decisions not to bring charges, discontinue proceedings, or offer no evidence in cases, should use the Victims' Right to Review scheme (VRR).

2.3. The IAC can consider the service elements of 'hybrid' complaints: for example, those that embrace both legal and service aspects.

2.4. The IAC will not consider service complaints relating to live or ongoing criminal or civil proceedings. Such complaints may be considered once those proceedings are completed. This includes cases that qualify under VRR but have not yet exhausted all stages of the scheme.

2.5. The CPS must signpost complainants to the IAC following the completion of Stage 2 of the complaints procedure (Complaints linked to ongoing civil proceedings must be deferred until the conclusion of all civil proceedings).

2.6. Complainants can contact the IAC directly where the CPS has not followed its complaints procedure, even if Stages 1 and 2 have not been completed. This could include circumstances where poor complaints handling at Stages 1 and 2 gives rise to further complaint.

2.7. Complaints must be submitted within one calendar month of the Stage 2 response. Where there are exceptional factors, the IAC may accept a complaint outside of this time limit.

2.8. The IAC also supports the effective implementation of the CPS Feedback and Complaints policy, overseeing the process and supporting the CPS to develop best practice and improved service standards for victims and witnesses. The IAC will be consulted on any substantive amendments to CPS Feedback and Complaints policy. The IAC will also be consulted on any substantive amendments to CPS Goodwill Payments guidance.

2.9. The Victims' Code outlines victims' entitlements to ensure that services recognise and treat victims in a respectful, sensitive and professional manner without discrimination of any kind. Victims are entitled to make a complaint if their entitlements under the Code have not been met.

2.10. The Attorney General may commission the IAC to undertake bespoke investigations on behalf of the Attorney General's Office or the CPS. The nature of these investigations may fall outside the usual IAC remit; in such cases specific terms of reference for the review will be drawn up.

2.11. The IAC will be supported by CPS staff (the ‘IAC Assistant’) who will provide executive support and advise the IAC on the eligibility of complaints under these terms of reference, although ultimately it is for the IAC to decide whether to accept complaints.

3. Review Process and Time Standards

3.1. As an independent post holder with quasi-judicial functions, the IAC sets their own procedure. However, in general an IAC review will consist of an examination of the papers at Stages 1 and 2 of the complaints procedure and any other relevant information.

3.2. The IAC will acknowledge receipt of complaints within 3 working days.

3.3. Once the matter has been assessed by the IAC Assistant and initially accepted as a service complaint, the relevant CPS Area/Central Casework Division will prepare and submit the relevant paperwork and a background note for consideration by the IAC. The IAC will consider the information provided and where necessary request further information.

3.4. Following consideration of all the information supplied by the CPS Area/Central Casework Division and any other relevant information, the IAC will decide the extent to which any part of a complaint should be reviewed. In so doing, the IAC will keep in mind the public interest. Factors against a detailed review include:

- The CPS Area/Central Casework Division has conducted a proportionate and reasonable investigation of the complaint and has found no administrative failure or mistake.

- The essence of the complaint is the complainant’s objection to the content and/or the outcome of CPS policy or legislation.

- It would be disproportionate for the IAC to review a complaint in detail.

3.5. The IAC’s review will be in the form of a report, a letter or whatever other form they judge most appropriate.

3.6. Where a detailed review is required, the IAC will send to the relevant CPS Area/Central Casework Division a draft response within 30 working days of the complaint being accepted by the IAC to allow for fact-checking. For the purposes of this paragraph ‘accepted by the IAC’ means where the IAC has informed that IAC Assistant that the complaint has been accepted.

3.7. The CPS will have 5 working days to respond to the draft report. Where further time is required to respond, this must be mutually agreed in advance of that deadline.

3.8. A full response will be provided to the complainant within 40 working days of the complaint being accepted by the IAC. If it is not possible to complete the review and reply within that timeframe, the IAC will contact the complainant to explain why there is a delay and provide a date by which a response can be expected.

3.9. A final report, once sent to the complainant, will be sent to the Private Office for the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) and Chief Executive Officer (CEO). They may also be sent to the relevant Chief Crown Prosecutor / Head of Division.

4. Remedies and Compensation

4.1. The IAC can recommend redress including: an apology by the CPS; changes to CPS policies and practices that could help prevent a recurrence of the circumstances giving rise to the complaint; a ‘good will’ payment in line with the CPS Goodwill Payments guidance or a referral to the CPS Civil Litigation Team.

4.2. The IAC cannot recommend disciplinary action against CPS staff but may recommend that the case for disciplinary action is considered under the CPS HR procedures.

4.3. Recommendations will be made to the DPP. The IAC's recommendations are not binding, but if the CPS decides not to accept a recommendation it will explain its decision in writing to both the complainant and the IAC. The IAC will report annually on recommendations not accepted.

4.4. Victims may refer their complaint to the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (PHSO), via an MP, following the IAC review, where they remain of the view that the CPS has failed to meet its obligations under the Victims' Code. Where there appears to have been a breach of the Victims’ Code, the IAC will notify complainants of their right to consideration by the PHSO.

4.5. Complainants who are not victims of crime cannot access the PHSO; the IAC review is the final stage of the complaints process in these cases.

5. CPS Responsibilities

5.1. The CPS will provide the IAC:

- Open access to complaints and feedback systems and records.

- Unrestricted access to such information required for the purpose of conducting a review.

- Executive support.

5.2. The CPS will ensure that the referral process for the IAC is clear and accessible for complainants and that the executive support arrangements are robust. Fact-checking of draft IAC reports will be undertaken within timescales as stated in section 3.

5.3. The CPS will formally acknowledge IAC reports and recommendations and provide confirmation by letter whether the recommendations have been accepted and implemented.

6. Reporting Arrangements

The IAC will provide reports (at least annually) to the DPP, CEO and the CPS Board. The CPS will publish the IAC's annual report on its website.

7. Contact Details

7.1. Independent Assessor of Complaints for the CPS

c/o CPS, 102 Petty France, London SW1H 9EA

Email: [email protected]

8. Review Period

8.1. These terms of reference will be reviewed annually by the IAC in consultation with CPS Private Office. Any changes proposed must be agreed by the CPS Board.

Crown Prosecution Service

May 2023